Like Neville Chamberlain before you, you have the opportunity to hold in your hand a piece of paper. And, per page at least, it could have fewer lies on it. Why not buy 101 Things Birmingham gave the World right now? A fantastic Christmas gift.

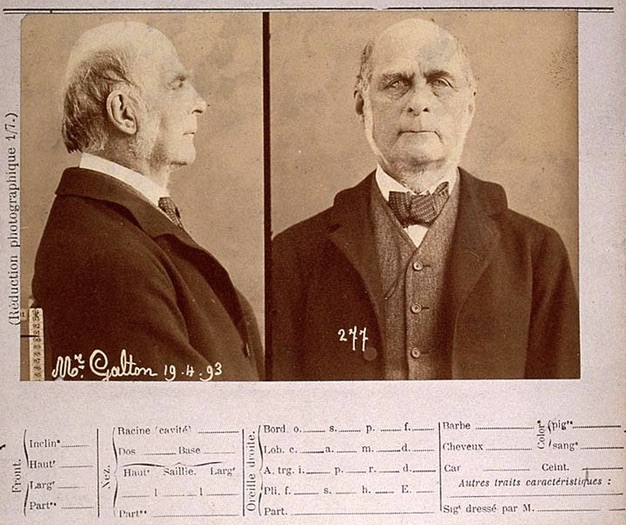

But there wouldn’t be books about Birmingham without the work of the 18th century’s Thomas Warren, who was the first publisher to come from Brum: and let’s face it no-one from anywhere else was going to publish them.

From his house over the Swan Tavern on the High Street, he founded a modest book making empire, and eventually a book shop. No records of the shop remain, or of any other independent bookshop in Birmingham at all.

Warren edited and published Dr. Samuel ‘Dictionary’ Johnson’s first book – a translation of Jerónimo Lobo’s Voyage to Abyssinia – which was a huge success and sold hundreds of copies, absolutely none of which ended up for sale second-hand at Reader’s World.

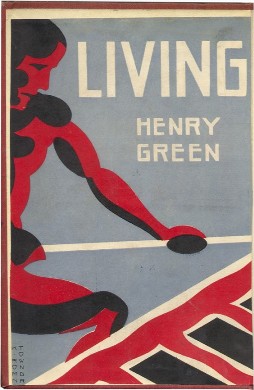

Without Thomas we’d never have had: David Lodge’s campus novels which pretend not to be set in Birmingham, Alton Douglas’s Dogs In Birmingham, Jonathan Coe’s Rotters’ Club, Henry Green’s Modernist classic Living, Washington Irving’s Bracebridge Hall (set in Aston Hall), Benjamin Disraeli’s 1845 novel Sybil which uses Birmingham as a background political barometer, or the wonderful work of Catherine O’Flynn. Nor this one, which has been called “wiser than it seems” by non other than Solihull’s Stewart Lee.

He also founded and published the Birmingham Journal – in 1732 – our first newspaper, and a hard slog that must of been too as there were no existing papers or websites in the city to copy content from.

Three cheers for Thomas Warren, a man who managed to change the world, despite living over a pub.

This is the book that proves that Birmingham is not just the crucible of the Industrial Revolution, but the cradle of civilisation.

It’s the definitive guide to the 101 things that made the world what it is today – and all of them were made in Birmingham.

Read how Birmingham gave the world the wonders of tennis, nuclear war, the Beatles, ‘that smell of eggs’ and many more… 97 more. It also includes a foreword by Stewart Lee called ‘A Birmingham of the memory,’ all about his relationship with the city.

“101 Things Birmingham Gave The World, is not a Birmingham of the memory. It is a living breathing thing, wrestling with the city’s contradictions, press-ganging the typically arch and understated humour of the Brummie, and an army of little-known facts, both trivial and monumental, into reshaping its confusing reputation.”

Stewart Lee

- You can buy the book on Amazon – in paperback.

- Or on Kindle here and get a digital one straight away.

- If you’re an Amazon refusenick, you can get an epub version here.