The history of popular music is the story of youth, sex, drugs and revolution.

It’s also the story of the ruthless exploitation of naïve young dreamers by savage and unscrupulous media professionals, a long process of vertical integration by global entertainment conglomerates, and the development, packaging, and marketing of products to carefully constructed and controlled sets of audiences.

As Hunter S Thompson said, “the music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There’s also a negative side.”

Or, as Les, former bassist with the luckless band Creme Brûlée from The League of Gentleman, put it with more slightly more brevity, “it’s a shit business”.

However, what people mean when they talk about ‘the Music Industry’ in these negative terms is often the large and successful parts of the recorded music business, and not all the other, sometimes benign and noble, stuff that happens elsewhere in what we should more accurately refer to as the Music Industries.

The recorded music business, as the name would suggest, is organised around the central idea of ‘the record’, and for that we must go back to Thomas Edison, who successfully managed to record the sound of his own voice saying the words ‘Mary had a little lamb’, in August 1878, and set in motion a chain of events that would eventually give the world The Spice Girls.

But there is also a positive side: the record, or ‘the pop song’, is the most democratic and versatile piece of art there has ever been.

It is the soundtrack to millions of lives, charts our loves and losses, and something that follows us and keeps us company from our wide-eyed, exuberant, youth to our befuddled and doddery old age. The experience you have when you hear a song is no more or less valuable than the experience it gives to millions of others. It’s a Living Thing, as a famous Brummie once said, available to all, mostly cheap and, even when the songs themselves are sad, ultimately very, very, cheerful.

Edison kickstarted a process whereby musicians and singers could commit sound to permanent record that could be played back across time and space. Originally in the shape of wax cylinders, then in the form of actual records (made of various materials, but eventually vinyl), and then assorted other formats across the 20th century and into the new millennium. The process of committing glorious noise to ‘record’ has similarly evolved over time, from speaking into a horn, as Edison did, to multi-track tape recorders in fancy, expensive studios, to pinging music to collaborators across the world via the internet.

Much has changed since August 1878, then, but one thing has remained largely constant in the face of all these technological developments, economic progress and changing social conditions: pop songs are still (usually) under four minutes long. They have been for as long as anyone can remember, and probably always will be.

According to The Billboard Experiment, which analysed and then visualised sales charts and song information dating back to the birth of the pop charts, the average length of a hit record in the 1950s was 2 minutes and 36 seconds. Even though technology has developed at a huge rate since those days, the average length of pop songs today is still under 4 minutes and 30 seconds. Why is that?

It certainly has some roots in the restrictions of the technology of earlier times, both in terms of recording and playback mediums (you can only fit so many grooves on a record, after all), but the idea of pop being short, sharp and simple has, nevertheless, stuck.

Verse, Chorus, Verse, Chorus, Middle 8, Chorus, Chorus – done. It’s a straightjacket we no longer have to wear, but still do willingly. And, because of these restrictions, the restrictions of music itself, and of the copyright industry that underpins the business of recorded music, pop has had to be endlessly and fabulously inventive. That’s why pop is great, bab.

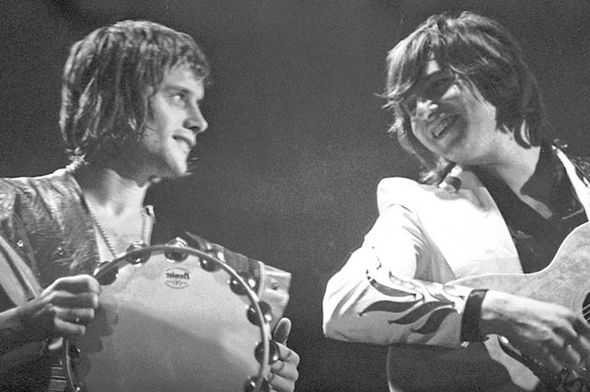

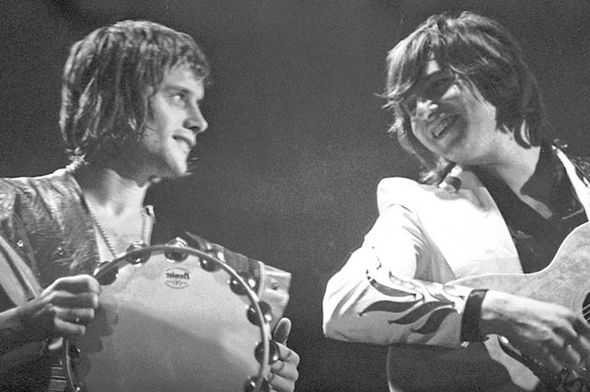

There is, however, one particular point in the history of pop music when this brevity was temporarily bunged out the window, along with the idea of pop being a democratic, public art form belonging to us all… and that moment was called progressive rock, or prog.

Prog grew out of the notion of pop singers as artists that emerged in the 1960s around the likes of The Beatles and Bob Dylan. That, along with advances in studio technology and the realisation by the recorded music business that they could make more coin this way, led to the concept of ‘the album’ being the purest and highest form of the pop art.

From Sgt. Pepper it wasn’t too great or long a leap to the idea of rock musicians as virtuosos, aloof and apart from the punters who worshipped them, of rock as high art that could only be understood in terms of it’s ambition and scale. And also to Rick Wakeman’s King Arthur on Ice.

Prog was endless noodling, complicated suites of music, and lyrics based on the worst kind of hobgoblin bothering nonsense imaginable, made by musicians from often highly privileged backgrounds. There were those that battled against this indulgence, including the caretaker of Birmingham Town Hall who locked up the organ and took the key home the night that Keith Emerson (of Emerson, Lake and Palmer) tried to play it – but it went on.

Prog eventually bored everyone so silly that we were forced to invent punk rock, which was also shit, but a least it was short shit, and that meant that everything was right with the world again.

Where on Middle Earth would a bunch of University-educated show-offs get the idea that people would be interested in overly-long fantasy bollocks? Step up to the mike, and strap on that double-necked guitar, J.R.R. Tolkien: the Brummie who hated Birmingham — who do you think the orcs are? — and almost helped to ruin pop music.