The commonly held view of 1960s popular music is that it was the decade during which the rulebook was torn up. Out of the dull austerity of the black-and-white 1950s the youth of the following decade exploded as one in a Technicolor riot of mind-bending drugs, free love and revolutionary fervour. If you can remember it, you weren’t there.

It was The Beatles who led the charge and provided the soundtrack, and nothing was ever the same again. As if to illustrate this point, Birmingham would give the world Heavy Metal by the end of the decade. But that’s another story.

What this version of 1960s pop history doesn’t tell us is that the rampaging youth were only part of the tale. There were also a lot of other people around in that decade, and many of them didn’t much care for The Beatles and all they brought with them. Mostly these naysayers were drawn from the older generation (and in the 1960s, this meant anyone over the age of 21), and it rarely troubles the history books that they too, just like their younger counterparts, bought and listened to a lot of records.

What did these people want from pop music? It certainly wasn’t sex, drugs and rock n roll played by long-haired oiks, that’s for sure. Indian spirituality? Womens’ Lib? Not their cup of cocoa.

No, what they wanted was simply something pleasant they could tap their feet to: in a word, they wanted something nice.

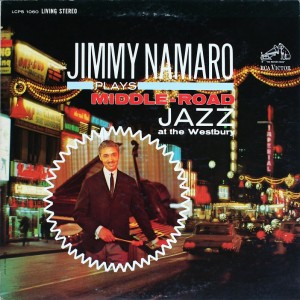

That something nice came in the form of string-laden arrangements of pop hits, songs from the musicals, and movie soundtracks. No rough edges, and no feedback. It came to be known as Easy Listening, and the undisputed King of the genre was Annunzio Mantovani, or, as he was more commonly and simply known: Mantovani.

Mantovani had shifted a lot of records before the 1960s even began. At one point in 1959 he had no less than 6 albums in the US Top 30 at the same time. This success continued throughout the 1960s, when he became the first artist to sell a million stereo LPs, and with scarcely a burned bra in sight. In 1970, ten years before his death and a full four years before Kraftwerk hit upon a similar idea, he released Music For The Motorway, a suite of lushness inspired by the mundane joy of motorway travel. Travel sweets and driving gloves. Nice.

In terms of record sales, Mantovani was a behemoth. Remarkably, none of his light-orchestral unit-shifting niceness would have been possible without the city of Birmingham.

In 1923, at the tender age of 18, Annunzio had cut his conducting teeth leading orchestras in the posh hotels of the city. The musicians he controlled were of a much older vintage and often included his father, Bismarck Mantovani (crazy name, crazy guy). Eventually, as with many Brum inventions before and since, the gifts outgrew the city of their birth and Mantovani was lured first to London, and then on to fame and fortune in the wider world.

Noice, bab.