You can be fashionably late to a party – arriving after the nominal start, when everyone is warmed up and in the swing of things, lubricated by the richest pickings from the drinks table, kitchen counter, or bath full of ice. But you can also arrive unfashionably late, when people are tiring, feeling jaded, and all that’s left to drink is a two year old bottle of Bailey’s.

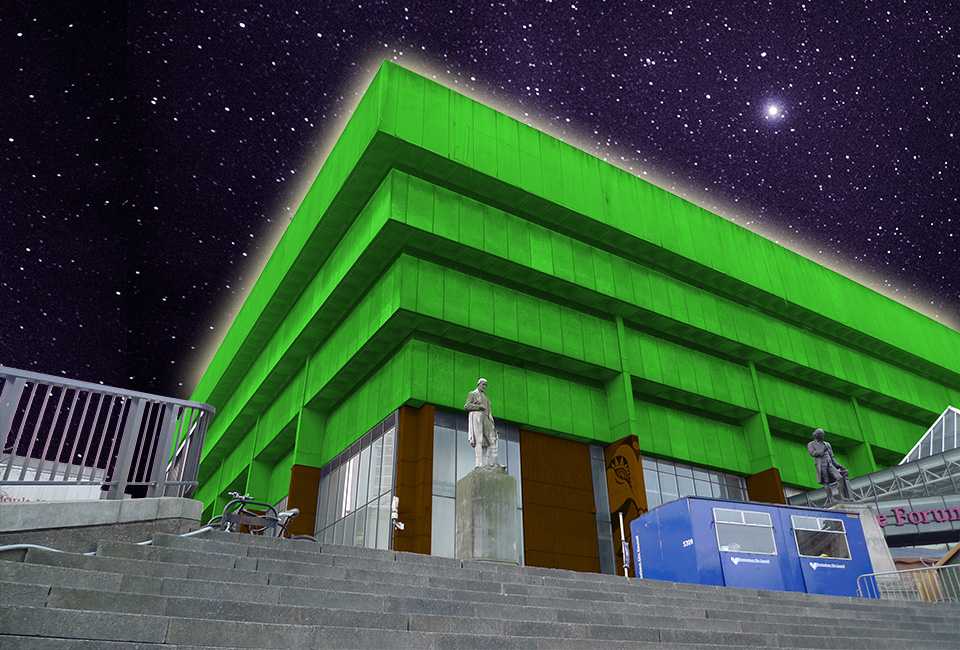

I’m unfashionably late to the Library of Birmingham. Like a pub worker who had to clean down then jump in a taxi to catch the last hurrah of the night, I come to the LoB three weeks later, making a metaphorical 2am appearance at its launch party. The bunting and the zany have all gone. The spectacles that caught the lenses of the media and the instagrammers have slunk off, leaving the library naked with only its truth to present to me.

The foyer has the feel of an airport terminal, with desks for the checking-in (and out), escalators that promise to pull you up into the business end of things and a bespoke unbranded eatery that offers generic options at air-side prices. The only way is up, and I’m pulled into the feature rotunda that I’ve heard so much about. It reminds me of Waterstones in the Pavilions centre, the area which was sort of modelled to make it feel like a library. I feel these two design conceits clash – the bookshop like a library, the library like a bookshop – and I’m lost for a moment to make sense of where I am, what this is for. I’m jostled by a group taking photographs. I move on to find a place where I can work.

I found that Central Library was a wonderful place to read, study and write; Central’s work area, with its bashed up desks, was unambiguous and surprisingly user friendly. You had a chair, a light, a plug and you were insulated from the outside world – buried in the centre of walls of books, hidden from the light and the view. The LoB works the other way, throwing you out from its centre to sit in brightly lit study areas in gallery windows that throw attention not onto the job in hand but onto Birmingham. I’m Goldilocks now, trying to find a seat: this area is too hot, this private study room has no clear booking rules, but this area, at the back, is just right. I look out onto tower blocks and concrete car parks and I get a glimpse of Paradise Circus. The LoB is a reaction to those things, a rejection of that vision of a city and yet in truth she is hemmed in by them. For now.

Another thing, there’s an edge here that I’m not used to. Phones go off, bodies stiffen. There are sighs, people obviously relocating to remove themselves from disruptions. I see an argument developing about a booked computer even though others are available. There’s clearly an old library crowd (am I amongst them?) and a new one, and they are still finding ways to accommodate one another. All of them are learning the building, and the building is learning all of them. Soon the building will have to react to them. Somewhere a laminator is waiting to make some signs (set in Comic Sans) to stick up around the place, to clarify functions and to formalise the new codes of the new building, the ones an architect and a designer can’t plan for. The LoB will be all the better for that. It needs a few scratches, knocks and dents, it needs to become less popular, less of a destination, before it can do its job.