The Electric Cinema is very flammable.

There was a time when all cinemas were highly flammable. In olden times all buildings were tinderboxes, of course, but cinemas had the added flair of being full of nitrocellulose (that’s film stock to you and me), a substance capable of spontaneous combustion and which, once lit, actually feeds itself by handily producing oxygen while it burns.

The Electric Cinema opened in 1909 and still has not caught fire.

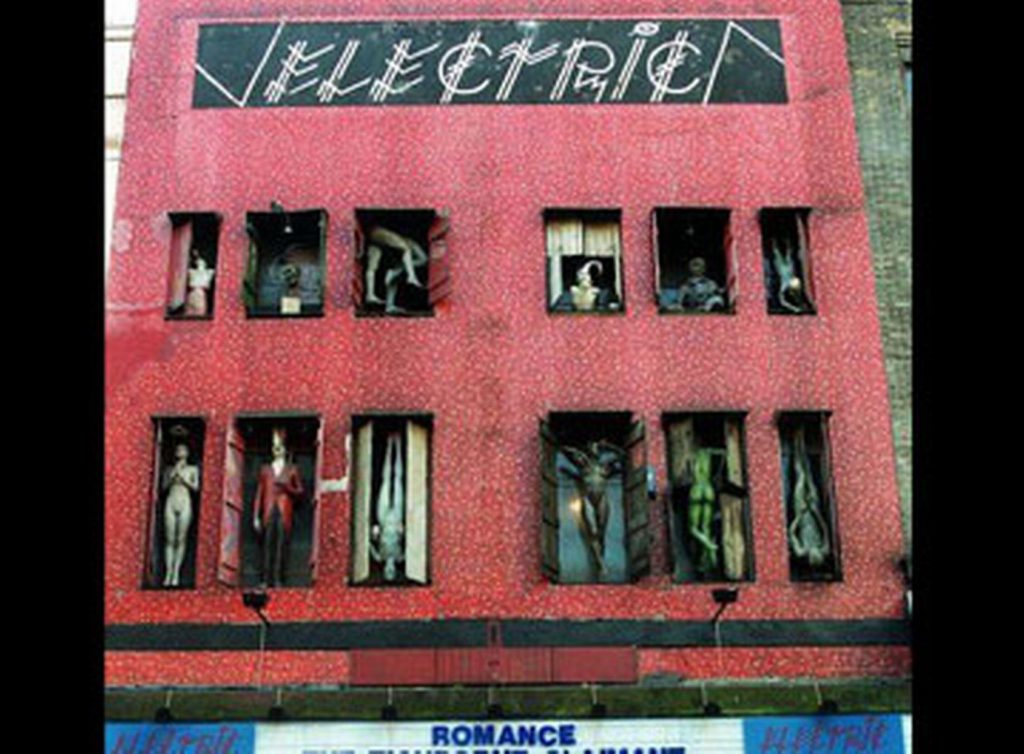

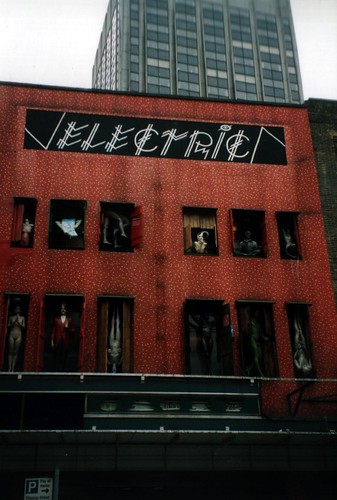

I first knew The Electric Cinema in its late 1990s incarnation. Painted in dappled burnt orange, with zany 80s signage, and featuring the terrifying art installation Thatcher’s Children by John Buckley (a series of macabre mannequins, hanging out of windows on the same level as the old New Street Station exits) it was quite an intimidating proposition from the outside — like the weird new kid at school with the too-big leather jacket, dyed hair and anachronistic musical tastes inherited from his older brother who lives away (is he in prison? The Army? Dead?). But much like that weird new kid, if you could get close to it, it was actually lovely. Weird but lovely. At The Electric in the 90s they had homemade cake alongside their terrifying statues.

It’s the oldest working cinema in the country. This is a fact. It’s a fact that is frequently disputed, but it’s a fact nonetheless: The Electric is older than the rest, and also has not burned down yet.

In the early 2000s The Electric closed down. It left a hole in Birmingham’s cinema scene as there were few other venues programming anything much outside of mainstream multiplex fare. It also left an empty and somewhat combustible building on a plot of land bang in the city centre.

Empty buildings have had a habit of burning down in Birmingham, especially those that might be in the way of progress (progress in the form of city centre apartments and mixed-use developments). It’s a fate that has befallen many old pubs, factories, and cinemas too so you’d have been forgiven for expecting to read some sad news about The Electric back in 2003 but, like a phoenix without flames, The Electric came back from closure unharmed, renewed even. Restored and resplendent in an Art Deco makeover-cum-restoration, The Electric surged back into business in 2004 with a mix of mainstream movies, arty stuff, and they even still had cake!

Under the ownership of a chap called Tom Lawes, The Electric saw its way through to its centenary year in 2009. Our own Jon Bounds attended a special 100th birthday party at the cinema and reported back:

Tom showed a great deal of the refurb work that’s gone into turning the cinema back into an inviting place in recent years — the roof and the plumbing seem to have contributed to it pretty much falling down. I felt a bit uncomfortable with the way in which the previous owners/management were obviously seen. Business-wise they were crap no-doubt, but for a while at least they brought all manner of esoteric, odd, niche and arty films to Brum — I have fond memories of dozing during triple bills of Italian films in the mid to late 90s.

To further celebrate, Lawes put together a film about the history of British cinemas, and The Electric’s place in that story. The Last Projectionist, which came out in 2011, has been described variously as an award-winning documentary and a “nostalgic advertorial” for The Electric but further cemented Lawes’s stock as Birmingham’s charming man of cinema.

The Electric of this era brought a sense of occasion back to going to the cinema. As a visitor you wouldn’t need to know the deep lore of the place for it to feel special — the history is there in the bricks, it’s palpable. Beyond the mise en scene, The Electric worked harder than most for you to have a nice time, with little extras like bar service to your seat and the big squishy sofas at the back of the room. Chains such as Everyman — which opened a Birmingham cinema in 2015 — compete with this luxury experience, though, offering more and squishier sofas, drinks and food service, and that weird thing where a handsome man stands at the front of the room before the film to introduce it. Everyman’s interior designers have reached for opulence: it’s all dark wood paneling and chintzy lights, a sort of speakeasy 1930s vibe — like someone poured the aesthetic of a George Clooney Nespresso ad into a multiplex — but they’ll never have the history The Electric has and so Birmingham’s Everyman will forever be a concrete unit in the Mailbox doing dress-up.

Slightly more expensive seats and a slightly more curated programme made this era of The Electric a pretty safe bet for date nights for the well-heeled, and the restoration style of the refurb perhaps helped it catch an updraft of cool cachet, as the whole vibe chimed well with the growth of interest in all things vintage.

Whilst it relied on bankable fare from blockbusters that were lighting up the box office, it kept a toehold for itself and for the city in the more artistic and alternative end of cinema too. For example, my all-time favourite cinema trip was to see Oxide Ghosts by Michael Cumming at The Electric.

Oxide Ghosts is a documentary about the Chris Morris TV show Brasseye, which was made with Morris’s blessing, on condition that it was only ever shown in cinemas and only if Cumming physically took it there himself and spoke about the film at length before and after it was screened. The whole setup for this is an incredible piece of self-curatorship by Chris Morris which, for me, beats even Morrissey’s insistence on having his autobiography published under Penguin Classics as an example of artistic shit-housing. Oxide Ghosts could only really show somewhere like The Electric because The Electric can make decisions locally, flex its programming to suit, and is big enough to make the showing worthwhile but also small enough to sell out such a weird event.

This is what is so delightful about this historic place: it allows Birmingham to stay connected to a world of film outside of what’s on offer at Great Park Rubery or Star City. And as a fixture of Birmingham for over 100 years, almost everyone has stories about going there, but if your dad has stories from the 70s they’re mucky ones…

If the post-2004 Electric was loved, its new owner, Lawes, was too. Saving The Electric (and serving fancy gin and lovely cupcakes) keeps you onside with the Evening Mail and would also go on to delight the slightly breathless #WowBrum faction of content posters who emerged in the 2010s to catalogue the nightlife and culture of our city. But Birmingham does love to build people up and knock them down, and some people like to bring their own hammer to help. When the Covid-19 pandemic forced cinemas to close, Lawes made his staff redundant when they could have been kept on under furlough and was roundly called out for his behaviour. Worse would be still to come, as the website for the cinema was replaced with a message that read:

The future of The Electric Cinema Birmingham faces an even bigger issue than that of Covid due to the impending end of its 88 year lease.

As the freeholder has yet to make a decision about its plans for Station Street, we are not currently in a position to reopen the cinema.

This uncertainty has also meant we have been unable to apply for the Cultural Recovery Fund or other financial support to assist us financially through the period of closure.

The subtext in the note: they’re coming for this historic and flammable building, I’ve lost.

Tom Lawes had been more than happy to criticise the business acumen of The Electric’s prior stewards, but it seems he may have succumbed to the same problems in the end. It will always be true, though, that he saved the UK’s oldest working cinema from dereliction (and probably a fire) at least for a while.

As with a disgraced pop star or movie maker, even if ultimately we feel let down by Tom Lawes we have to say: his work still speaks for itself, his work still stands — and The Electric still stands, un-burnt down, flickering its story onto the screen again and again, its projector a light that never goes out.

When I first wrote this for the publication of Birmingham it’s Not Shit: 50 things that delight about Brum, it seemed that The Electric would continue again. New heroes emerged to bake the cakes and load the projectors, in the form of the Markwick family who owned a not-quite-as-old cinema in East Sussex. The Marwicks took on the Electric and successfully reopened it in January 2022.

Unfortunately, their tenure seems to be coming to a close—and for reasons Tom Lawes foreshadowed, around the end of the lease, according to Flatpack

At the end of March the building’s current 88-year lease will come to an end. We understand that a property developer intends to apply for planning permission to demolish most of Station Street – except for the Grade II listed Old Rep Theatre – to make way for a fifty-storey apartment block.

Nonetheless, at the time of writing, The Electric Cinema has not yet caught fire.