It’s an incontrovertible yet nonetheless contested fact that Birmingham’s Electric Cinema is the oldest working cinema in the UK. Birmingham can, then, claim an important part in the history of cinema in Britain. The Electric, though, is a peculiar beast. Those who would dismiss its claim to be an historic venue might point out that very little remains of the building of 1910, and so look instead look to the South East – to Brighton’s Duke of York’s or London’s Phoenix (née the East Finchley Picturedome). Of course, it better suits the accepted narrative of arts and culture that such things would belong to the capital or its artistic dormitory town, so The Electric is easily brushed aside by historians and journalists.

In explaining to you how Birmingham invented going to the pictures I will also brush aside any mention of The Electric because going to The Electric is not, you see, going to the pictures.

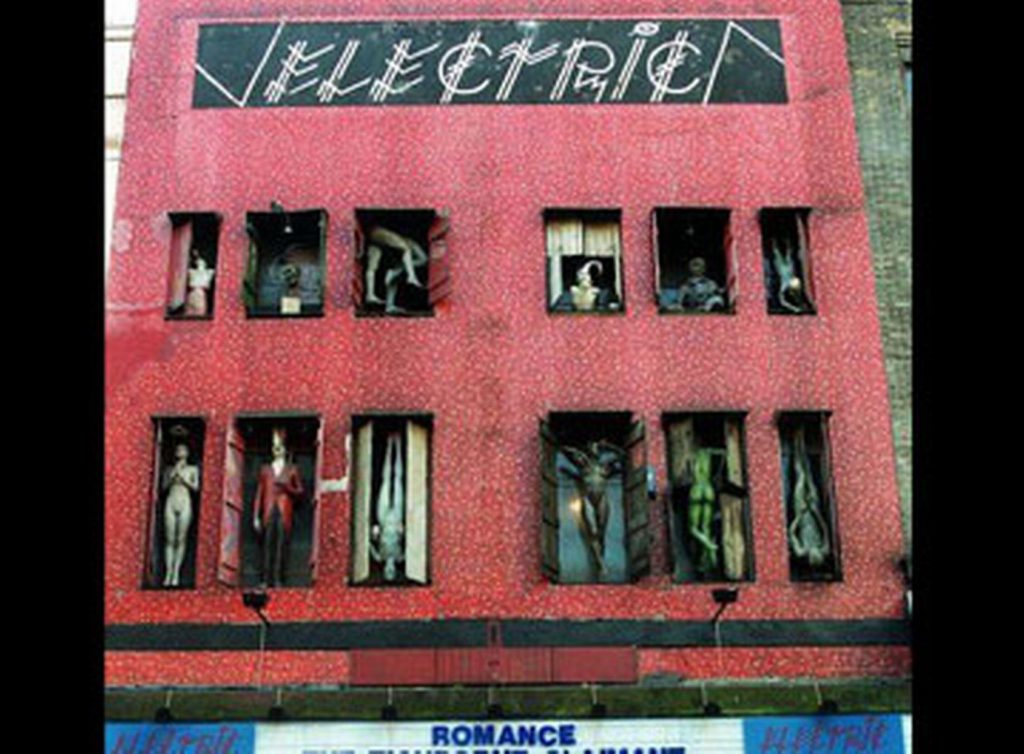

The Electric has had many uses in its lifetime but has primarily had two incarnations: one as a smut house, and the other as an art house (which is often similar to smut but has better lighting and subtitles). It is more conventionally known for the latter and essentially trades as such today. The thing about The Electric, though, is that it is not a place where one goes to the pictures: it is a place where one demonstrates distinction when watching cinema releases. What do I mean by this? The Electric’s thing is to be a little more expensive then the rest and by being so to promise you things you don’t get down the multiplex: nice food, beer (brewed by a micro brewery just a few miles away of course), a decent selection of scotches, a big squishy sofa and beautiful hipster staff who bring you olives if you send them a text. It is categorically not what happens over at Rubery Great Park where you can buy nachos with plastic cheese and a 2 litre cup of pop from a (rightfully) angry minimum wage teenager in a gigantic ‘90s-built metal shed. That’s for other people, we are better than that and we want to enjoy our film in the quiet THANK YOU VERY MUCH. The Electric does all of this whilst actually running like a mini-multiplex. For all of its art cinema posturing and pedigree it runs a programme of only the most bankable and accessible independent fare bolstered up by Marvel superhero franchises. In this regard The Electric and its clientèle can have their homemade organic carrot cake and eat it.

There is something about The Electric though, a certain glamour in the architecture within, that belongs to Birmingham and belongs to the story I need to tell you: how Birmingham invented going to the pictures.

What do I mean by going to the pictures? I mean cinema as a great democratised pastime, not the sort of middle class fussiness that goes on at The Electric today. Ironically, considering where we are now with the out-of-town multiplexes, it all did begin with a bit of glamour, a bit of glitz, which turned up on the Birchfield Road in Perry Barr.

It was here, in 1930, that Balsall Heath’s Oscar Deutsch opened the very first Odeon cinema. The Cinema Treasures history website describes the venue for us:

The facade was painted white and had rounded features that gave an impression of domes. Inside the auditorium seating was arranged for 1,160 in the stalls and 478 in the balcony. An unusual feature was that the stalls area widened out towards the proscenium. There were Moorish scenes painted on the side walls in the front stalls area.

Now Oscar had already opened a less glamorous Black Country picture house but with the Perry Barr Odeon he perfected the model for his cinemas. He decide to stick with the name ‘Odeon’ and hired the building’s architect, Henry Weedon, to design more of the same and then he rolled out his nascent chain to the rest of the country. Oscar had invented going to the pictures: a little bit of glamour and glitz, uniformed ushers, ice cream trays and intermissions, packets of Poppets or chews, an advert for a Chinese restaurant just a few hundred yards from this screen – it all started in Perry Barr.

Time moves on and over the years the model began to change. There’s less of the glamour now then there was before because cinema has been moved out of those beautiful Art Deco buildings into vast pleasure domes on cheap land out of town. But for a while there Oscar had brought a little bit of stardust to us all. Yes, going to the pictures was a wonderful thing but now all I’m left with is misty eyed nostalgia about what we have lost that leaves me sounding like a Peter Kay routine. Do you remember those cartons of drink they had? With the spiky straw? Not Capri Sun, the others. You had to stab the straw through and if you got it wrong it would bounce off. And Nerds? Orange and green they were. Do you remember? Do you remember? Sweets? When you were a kid?

So what became of Oscar’s dream? Well, other than a series of leveraged buy-outs and mergers that have remapped the network of cinemas and cinema chains, he left behind a lot of architecture. The smaller community cinemas of days gone, abandoned by the march of progress out to Star City and Rubery, left behind shells that needed to be filled. Such beautiful shells.

The fate of these buildings differs from place to place. In Asian neighbourhoods they have become banqueting suites, their mix of space and interior features making them perfect for weddings and special occasions. In poorer white neighbourhoods they are bingo halls, which turns out to be an even quicker way of taking folks’ cash than the obscene markup on cinema hot dogs; meanwhile in the boho white areas, those places with an upswing of gentrification, they burn these palaces to the ground so that they can fit in more flats and indie coffee shops. For anyone else, they also make a good Wetherpoons. You can chart the changes in communities over time by the uses of their old cinemas which change as demographics swing. Indeed that first ever Odeon, on the Birchfield Road, has been a bingo hall and is now a banqueting suite. It’s never caught fire but there was an awkward attempt to clear it by some Germans looking to spread their lebensraum in the 1940s – damage caused by their bombs led to the loss of much of the building’s Art Deco exterior and it was rebuilt in a much more austere fashion. In many ways we invented not just going to the pictures, but what to do when the pictures have gone.

This article is rated PG for occasional adult themes.