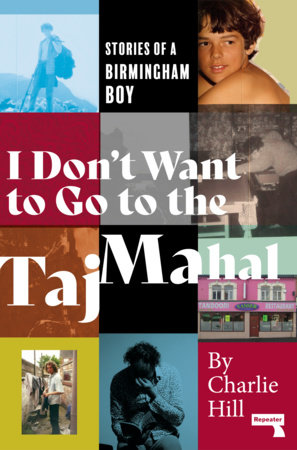

Charlie Hill’s I Don’t Want to Go to the Taj Mahal is a book about work, identity, sex, politics, drugs, homelessness and dissolution, but we feel it’s mostly about Birmingham at the end of the twentieth century. Enjoy this exclusive excerpt, and then go get more.

Working in a Victorian factory in Digbeth that made pelmets and curtain accessories, I bet every day with poor Irishmen in Bartletts bookies. During my first shift, I noticed a strong smell of almonds so I asked the gaffer, a bull of a man with mildewed suit cuffs and dried egg yolk on his tie, what it was. He pointed to two enormous open vats in the middle of the floor and said “those are cyanide baths”, and I heard them hissing.

I worked with a Brummie who supported Lincoln City — “because you can get closer to the action than at a First Division club” — and he was astute. Seeing that my heart lay in something other than counting tunnel brackets, he bet me a fiver he could count more in a day, a challenge I accepted, once at any rate.

Later I volunteered to drive a forklift, because it was the best of a shit job. All of the weight in a forklift — the battery, the engine — is at the rear end. Like a child in a toy I reversed it down a ramp, the weight took it out of my control and it toppled slowly off the edge. The only thing that stopped the forklift from going over on its side, with me underneath, crushed bones into concrete, was a metal post that bent to 45% and left it balancing like a metaphor for something, not that I had much time for metaphor at Harrison Drape.

I am a Christmas temp at H. Samuel, the high street jeweller, where a fella called Tahir puts me straight about the low quality of Pakistani gold and someone with blond hair and blue eyes – who looks after the Raymond Weils but is lacking in certain deductive skills – tries to sell me a part-share of a holiday apartment in Fuengirola.

Another temp lives in a tower block in Five Ways. I go back to his and am told that people who use rolling tobacco in their spliffs are amateurs. At lunchtime I see him in the store room, filling a sports bag full of watches and alarm clocks which he later passes to an old woman, hard-bitten; if I hadn’t been stoned I might have said something to someone, though I think, in retrospect, that’s unlikely.

Interviewed for a Registered General Nursing Diploma, I have a plan to show I’m under no illusions about how hard I’ll have to work and that I haven’t decided to do it just so I can get a qualification, although this is certainly uppermost in my mind. “I know it’s a very dirty business”, I say, “I’m perfectly happy clearing up shit”. And then: “I mean I don’t mind clearing up shit at all, I know that’s a big part of the job. The shit.”

“Any questions?” they ask at the end, perplexed. “Not really”, I say, persevering, about a week before I don’t get an offer because they think I have some sort of shit fetish, “I just want you to know that I don’t mind wiping bottoms and I’m prepared to get stuck in with the cleaning up of all the shit.”

New Year’s Eve, after the pub, I am escorted round the back of an independent bakery – Lukers, in Moseley – by a woman uninterested in pastries. I am being forced up against a pile of pallets when the security lights come on and she bails, a circumstance that leads me to question my hitherto rock-solid antipathy to the nascent Surveillance State.

First love. One day, shortly after the longest Christmas on record, there was a heavy fall of snow in the south west. “I don’t want to go to work today,” I said, and she said “you don’t have to. Tell them you went to Devon for the weekend and can’t get back.” So I rang a Civil Servant in the office where I’d just been promoted and told him I was snowbound in Tavistock.

We spent the morning warm under thin blankets, feeding each other fresh strawberries dipped in cream, mouth-to-mouth. Later, there was a cosmic blessing. The clouds above the city opened and dropped flowers of snow onto streets of cars and terraced houses and we went for a walk down the middle of Willows Road, linking arms like the Freewheelin’ Dylan and Suze.

Publication! At the first time of asking! The Observer Magazine pays a third of my monthly take-home for a rant about Civil Servants being unable to think for themselves. I do some sums and calculate that if I sell three of these freelance pieces a month, I’ll never have to work again. So I pack my Civil Service job in, buy an electric typewriter and get to it.

It was my twentieth summer and I was living with a woman in Handsworth Wood and having doubts about our compatibility, including but not confined to her liking for Kaffe Fassett knitwear. I played cricket for the second team at Moseley Ashfield – Moeen Ali’s club! – and went on tour to the New Forest. The first night, I appropriated a straw boater from behind the bar of a pub in Brockenhurst and met a girl who took me camping in a clearing that was a wild pony rat run. We played pool together and drank English beers, but she read too much Terry Pratchett and there was nothing going on.

I broke the bad news to my lover a week later. A week after that my new friend visited to play pool and drink English beers, a misjudgement, it seems. My ex was furious and no one in the city believed a word I said.

An ex-girlfriend drove a lime-green mini. She had given it a name though I can’t remember what it was. I left the pub with another woman and walked her home to a tower block in Highgate, full of the bursting stanzas of youth.

The lime-green mini overtook us and my ex got out, berating. We walked on. The lime-green mini overtook us and my ex got out, berating. We walked on. The lime-green mini overtook us and my ex got out, berating. We took a shortcut through a park.