I don’t think I’ve ever taken a book out of the Central Library in Birmingham, nor used one for reference. I’m not really a library person. I used to copy CDs from there like everybody did before mp3s, and I’ve wondered around looking at the shelves, breathing the mites and the refreshing book dust. I’ve stroked the static and brushed the peeling selotape from the yellowing computers by the escalators. I’ve been frustrated by trying to use the photocopiers, toying with the intense flaccidity of the coin reject button.

I’ve done pretty much everything it’s possible to do in a library. And, like a good boy, I’ve done it all quietly.

But the prime function, no. While I love words I have an old fashioned compunction to own them. Imagine being in love with a story and having to give it away to be intimate with others who maybe wouldn’t love it as wisely and well. A library is nothing but a fountainhead of potential heartbreak. And Central Library had the potential to be the worst.

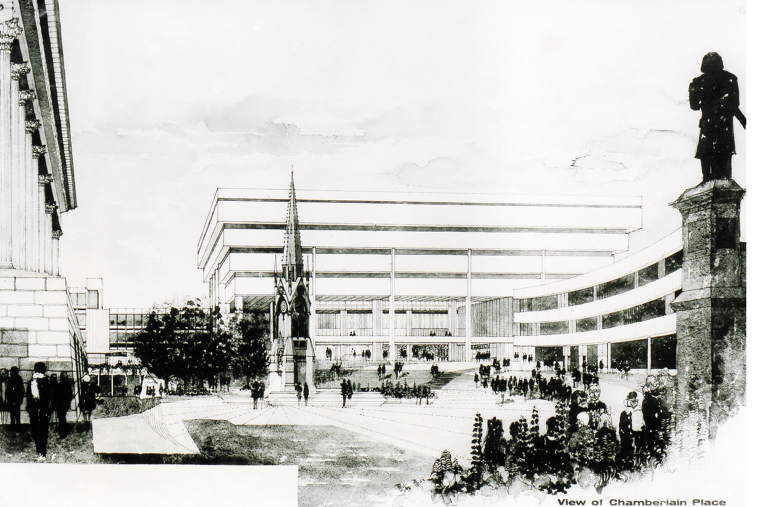

So maybe I shouldn’t care about what’s happening to Central Library: but I love the building, I love the size and the shape, I love the angles and the implausibility. I love the incongruity and placement most of all. Where-ever you stand it’s not possible to get straight on to its parallel lines. So whatever your view the building flows away from you, meeting at a horizonal distance, pointing toward the future and the past.

I like that it’s Central, in the actual usable centre of the city rather than somewhere as a ‘destination’. I like that it sits on top of a modern motte, steps and coiling ramps leading you inextricability into its mouth. For a building to fit into its surroundings doesn’t mean it has to blend in, just to create interesting and beautiful contrasts—the straightness that was forever peaking out from the overblown revivalism was refreshing. It allowed modernity to poke into the heavy set city, and to thrust into the sky. It was different and, unlike the swirl cladded replacement: truly iconic. That is it was an icon, one that reflected the town and acted as a code for it. That takes years and it’s something that shouldn’t be thrown away.

If a city doesn’t have the confidence to love something unfashionable then it’s doomed to look like a local radio DJ picking up on the trends just five minutes after they’ve appeared in the Sunday Times magazine. Yet, we have had for years the supposed guardians of the local culture stepping over each other to Gok Wan the city centre to death: to hide anything non-conventional and to spend as much money as possible on imitations of things other places have. As long as they have approval and a designer stamp.

Oh, and if the destruction and shifting away from ‘prime office space’ of a public amenity opens up potential for money, then all the better it seems. Don’t be fooled that anyone who’s had anything to do with the decision to destroy this building has thought for one second about architecture or beauty. They’ve thought only of how modern (rather than modernist) looks better as a backdrop for photographs, and how many more opportunities for canapés and wine there are with new buildings than there are with the upkeep and use of current ones.

The Council House will look worse without the Library as a backdrop and the inhabitants of the Council House look will look worse when we examine them in the harsh glare of their actions. They, like me, will regret its passing—whether they ever went in or not.

Image CC licensed from Architectus.