We all know that Birmingham isn’t shit. We’ve spent nearly 20 years telling people, showing the world, and often undermining our case. In our new book we lay out the ineffable reasons why we say ‘Birmingham: it’s not shit’ and attempt to eff it.

Cliff Richard is not from Birmingham; reason for celebration enough some might think, but they are cynics and have no place in this discussion. A fleeting mention of Cliff Richards makes me think of Birmingham and smile, for Cliff is somehow part of Birmingham — almost is Birmingham on another plane of existence.

The parallels are huge. We, as a city, are Christmas – we shine and glitter in a gaudy way. Cliff is too – he’s had four Xmas number ones to our one. We both love Eurovision – Cliff’s two appearances to our one outranks us – we both love women’s tennis and we both don’t get much sex.

When things aren’t going well for either of us, Cliff and Birmingham are drawn together against the elements. Celebrity indoor tennis tournaments give you something to do when the hits aren’t exactly flowing like water, and Birmingham can hold them like no other, when the newly-built arena isn’t being used fruitfully.

For me the symbiotic relationship between the city and the singer dates back to 1972. Cliff released a heavily religious single into a chart that was topped by Don ‘the other one’ McLean’s American Pie and Nilsson’s Without You.

“Jesus, won’t you come back to earth?” the song implored, which was the same thing that people said to the council when they again announced that Brum was bidding for the Olympics. It’s a very Brummie exclamation when you think about it: ‘Jesus, are they digging up Corporation St again?’, ‘Jesus, what’s Mike Whitby paid Capita to do now’ or simply ‘Jesus, have you seen that film where Cliff Bloody Richards drives a hovercraft under spaghetti junction?’

The 45 peaked at just 35 in the UK Singles Chart, Cliff’s second lowest placing in 15 years of hit-making. It can’t have been because the hit parade wasn’t ready for religion, because also in the charts that week was future primary school assembly hymn favourite Morning Has Broken. For a man enthused by the power of Christ to save us all, this must have seemed like rejection. Because despite a phenomenal Hank Marvin guitar line, it flopped and it was a rejection: Cliff released Jesus and wept. But when there was only one set of footprints in the sand, Birmingham was ready to carry Cliff.

And we were ready to lift him, right to the top of Alpha Tower. Take Me High was Cliff’s last film, he was to change from the young heartthrob and in 1973 redevelopment was all around the town too. Huge modernist blocks sitting side-by-side with the last bits of canal-dwelling culture.

Film Cliff wants everyone involved to join the band. He wants to hastily arrange a parade down Corporation St. He wants us all to meet at the ramp.

While Birmingham is on screen a fair bit these days, it wasn’t then – and to have a film that acknowledged it was set in the city was special. This one literally sung loudly from the rooftops about it.

Slade in Flame starts in the Midlands – although not filmed here – but as soon as Flame (the band Slade are playing) get success they are off to London. Privilege, the third in this sort of trilogy of Brum-pop films of the 70s – a dark counterpoint to Take Me High staring Paul Jones as a pop star puppet of the regime in a Anglican-facist Britain – is filmed in the Town Hall and even St Andrews, but it isn’t ‘Brum’. Take Me High is filmed and set in a particular Brum bursting with the sort of confidence that only big new buildings replacing the slums and bomb sites can be.

This is the Birmingham that we want to tell ourselves we were – in our history no gap between the Lunar Society, Cliff’s Brum, and then the modern gleaming shopping centre we became in the 21st century. Forward, the film cried.

It was also so forward-looking that the soundtrack contained a joke about artisan street food being ‘the biggest load of bull you’ll ever get’ – something we failed to learn from. The ironists took hold and you can now of course buy a BrumBurger at any number of ‘fairs’ and ‘dining experiences’ in the city. In my head the BrumBurger has protected geographical status – to be a real BrumBurger it has to be fried within the sound of someone rattling on about the 11 route, otherwise it’s just a generic metropolitan meat patty.

Despite all this, the film entered an almost Schrodiggian state of being forgotten and remembered at the same time. To start with it was really buried, talked about only wherever oddballs with an interest in local history met, but then like everything else it was remembered as something that is forgotten — the internet doesn’t mean that there’s no right to forget, but that everything is forgotten until it’s the right time for a local newspaper website to run a nostalgia feature. Do you remember things? Yes, and when I remember Cliff I’m happy.

Cliff really was trying to save us, and never more so than when he wanted to give us hope in a new millennium — and this made Cliff stand out from his contemporaries. Did Adam Faith try to save Manchester? Did Billy Fury decide to devote his time to letting us know that it was in fact Bournemouth that was a wondrous place? Was Joe Brown always going on about London? Yes, but that wasn’t the point. Cliff was rejuvenated by Birmingham and was ready to return the favour many times over.

An eternal flame, lit as a torch by the now Sir Cliff for world peace at the start of the millennium, sat on top of a huge metal globe in Centenary Square. The Flame of Hope was the idea of a group of churches across the city, but it was clear that no-one involved planning the flame had ever lived in a house where you had to think about whether you could afford to put the immersion on.

British Gas sent an estimated bill for £12,000 a year and when the meter was finally read the bill was red and the council turned it off.

“Obviously it was not for an eternity, we realised it had a lifespan but it was something other than just the excitement and dreams of one year,” said Reverend Mark Fisher, from Birmingham Churches Together who had put it up. Hope – for the time being – of a better Birmingham seemed extinguished too. But Cliff, of course, wasn’t going to take that lying down.

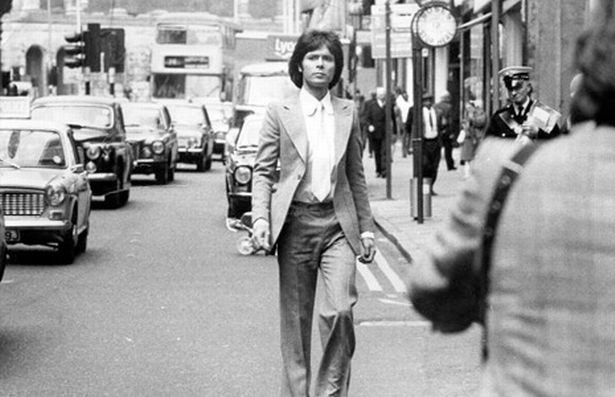

In December 2013 I woke to the clock radio featuring Cliff using Radio 4 programme Saturday Live’s feature ‘Inheritance tracks’ – a mini two-pick Desert Island Disks where the notable choose records that mean a lot to them – to send a coded message. He selected what he called “one of the greatest pop-rock songs of all time”: his own Wired for Sound. You know, the one where the video has him rollerskating round a concrete dream that could be the back of Central Library (it was in fact the centre of Milton Keynes).

By going against decorum and tradition, selecting his own record, Cliff was telling us to be more brash and self-confident. He was banging a drum and blowing his own trumpet both of which are difficult to do on roller skates.

Did we miss the nuance? Was the message more detailed? Should we have been more proud of being a ‘concrete city’ (as the song Working from Take Me High called us), or was it about ever moving forward? He liked tall speakers, he liked small speakers – should we have got ex-Blues striker Kevin Francis and Kenny Baker to do a joint speaking tour about their home town?

In the build up to the London Olympics, Cliff helped to carry the Olympic torch from Derby to Birmingham as part of the torch relay. This leads me to believe that Cliff wants to burn the city to the ground to cleanse us with fire. That, or he wants to stage the second biggest barbecue in Europe, give you a free burger and then talk to you a little bit about letting Jesus Christ into your life.

As the commonwealth’s ultimate trendy vicar — trying a bit too hard but ultimately well meaning and cool in the way only those that plough their own furrow can be — doesn’t Cliff Richard just remind you of Brum and why it’s not shit?