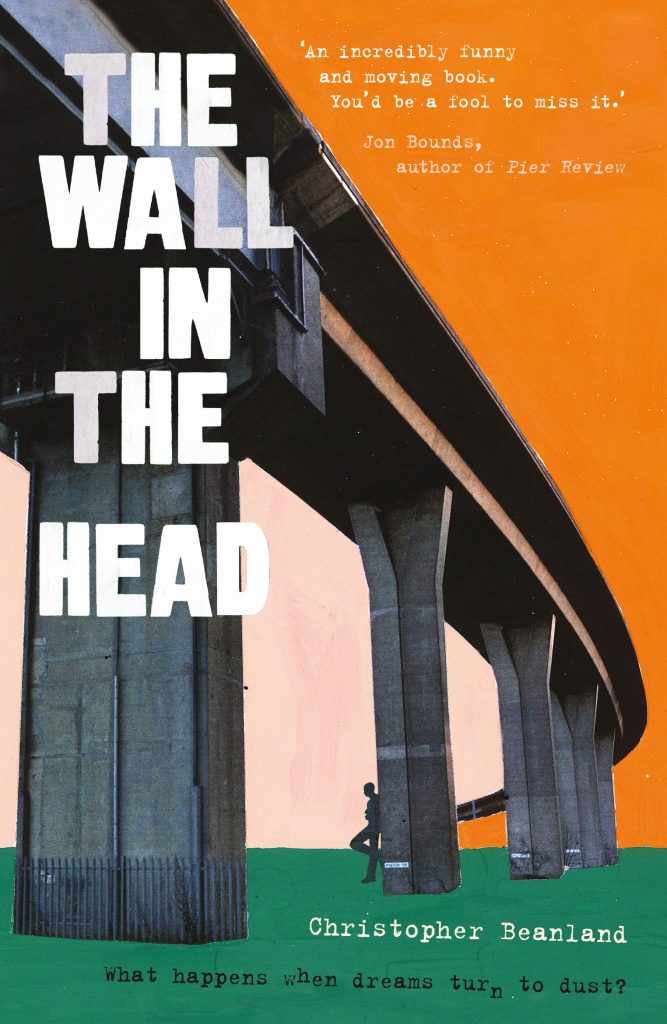

Christopher Bealand’s new novel is out this week, it’s ‘a black comedy about love, loss, the death of dreams, failure, bad TV, bad jokes, brutalist buildings. And Birmingham.’ And we have an extract so you can see that for yourself…

“Belinda the main, but absent, character in The Wall in the Head says she has written a book about ”love and architecture” and this too is a book about love and a book about architecture – or at least our relationships to them both. More than that it’s a book about our connections to place and people, and how they shape our feelings and actions.

“It’s a love letter to brutalist buildings and the sheer hope for humanity with which they were built, it’s a love letter to the places that are left behind by trends and culture and Birmingham as a prime example of that. It’s also a love letter to the idea of love and laughter but far more classy than those words painted onto the living room wall of your new city centre flat.

“Christopher Beanland has written an incredibly funny and moving book set in a decaying version of our past hopes, and you’d be a fool to miss it.”

Jon Bounds

Buy The Wall in the Head here.

The Wall in the Head by Chistopher Beanland – Chapter Two

I yanked the fridge door and it opened with a surprised gasp. Inside, a fragile light flickered in the dark. The fridge was empty, wiped, it stank of surgery – I’d cleared it out this morning in anticipation of my death. I didn’t want to seem like a monster – no one needs the spike of rotting food in their nostrils when they’re clearing out a dead bloke’s house.

I went upstairs to my desk, looked out of the window at the caramel street lights of Moseley, at the trees swaying back and forth in the high winds. I flicked on the computer and started writing about what I’d done tonight, but the words didn’t come easily. Words hadn’t come easily since Belinda had to ruin everything. When I could manage no more I lay down on the bed, staring at the ceiling. Sleep hadn’t come easily either, but tonight it ate me up. The duvet enveloped me; my eyelids slid shut like they were greased. I succumbed to the darkness and the solitude it promised.

*

This is a dream:

I can see. I’m part of the world I’m seeing – I’m participating, not just observing. I look down and I see hands. I twist them around, tensing and flexing. I’m alive, alright. It’s Birmingham. I’m watching a blonde-haired woman sleep. She’s lying on a bed in the middle of a roundabout overlooked by two tower blocks. It’s daytime but there’s no one else around. Just her. She’s dozing peacefully, curled into a ball, with golden locks falling across a face painted with a honey glow of serenity. I don’t think it’s Belinda. I think it’s someone else. I’m not sure. I wouldn’t put a bet on who it was – I can’t see well enough. It’s a dream; things are a bit fuzzy, misleading. It’s like watching through cataracts. I turn around and I see a new scene. A skyscraper stretching upwards into the sky like a sentinel. It’s made from concrete; its hue is deep grey, with jagged lines running up and down it, and different-sized blocks around the bottom. The Mids TV HQ. The studios and the bar at the bottom, the office tower stretching upwards. The office tower I just jumped off. Tension, fizzing, refracted sunlight, pickled emotions, streetscapes grey and green, no people, bridges red and brown, a heartbeat jumping, my heartbeat jumping. The same blonde woman is sleeping on the same bed below; she wakes and points up to the Mids TV Tower. Next scene. A thinner tower without windows – the BT Tower. The blonde woman is standing by it, wearing a knowing expression, looking a little like a witty English teacher? I turn a final time. One more scene. The same woman on a bed in the middle of an open-topped atrium space. There’s nothing surrounding us at ground level apart from twelve slender pillars. Above about the third storey there are concrete sides of a box with windows facing inwards to create a courtyard – but the roof is open and sunlight falls in like it’s being shovelled down onto us by a giant gardener. The woman wakes up, stretches her arms and sits up on the bed. She lights a fag. She turns and swings her legs down over the edge of the bed. Her face. A sudden crash-zoom in on her face. She looks at me, helplessly. She stares right into my eyes. Her mouth doesn’t move – but this sound comes out of it: ‘Donald.’ There’s a drummer in my chest, hitting so hard I can hardly concentrate.

*

Ten Brutalist Buildings

By Belinda Schneider (Published 2002)

Chapter One

Birmingham Central Library

Use your eyes. Listen to your heart. Two things interest me most: what does a building look like? How does a place make you feel? That’s it. That’s the secret. Architecture is really about the art around us, the art you spend your life inside – or outside, looking in at – and it’s about the things that happen there. Things that have happened to you. Things that have happened to all of us.

Life isn’t just fragmentary, it isn’t just fleeting. Put the little pieces together and mould them into a story. You can slot things together into a narrative jigsaw. Draw lines between feelings and meanings like art does, connect events and ideas like philosophy does. There is a purpose. Art explains the world. We as participants in art and in life can achieve something. And with these particular buildings, built at a particular time, we did try to achieve something – something for everyone. Something for everything. Perhaps brutalist buildings are the closest thing to a pure evocation of utopia that we ever achieved. Or tried to achieve, at least. These buildings, these places, were for the people and for the future. Public places where public lives were led, lives both sad and happy. That’s why I love them.

The first time I saw my future husband was inside the courtyard in the middle of Birmingham Central Library. There was no roof and no stupid fast-food joints back then – they were moronically added later. There was just a huge open space with cliffs of pure white concrete surrounding a cool plaza. Sunlight streamed down; the splash of water fountains and the chatter of people filled the air. I liked Birmingham because it was a city defined by its architecture and by its hopes. By the future, not by the past. It still is. People think of it as a place filled with certain buildings, certain types of buildings. They probably don’t like those buildings much. I do.

Important moments have to happen somewhere, and because they happen in a certain place or a certain building, then that place or that building is forever imbued with an importance that goes far beyond the structure, beyond bricks and beyond concrete. These places are the theatres where real-life dramas are played out. How many couples had their first lunch date here? How many couples had their first kiss here? How many couples had sex here? How many couples broke up while sitting on benches in these squares? You have to look around and feel these ghosts – the ghosts of the present, of the past, and of the future.

Here’s my story. Donald was dressed as a chicken. He’ll deny that, of course. But he definitely was. A human-sized chicken. He took his chicken head off and I stared at him for a while as I smoked a cigarette. He looked quite handsome, I thought. His mop of blonde hair was all scruffed up from being inside the chicken head, and his eyes squinted as they came to terms with the afternoon brightness. I liked him. He drank a can of soft drink, cola perhaps, put the chicken head back on and manoeuvred round so he was between me and the camera. He did this stupid little dance and handed out a few flyers to some passing office workers, then the director yelled, ‘Cut!’ A little later they filmed another segment, and after they’d done that Donald came over to me and asked me if I could do a Birmingham accent, and I tried but it was pretty laughable. I was glad he talked to me. I noticed he looked into my eyes for just a second too long while we chatted. It was a total giveaway. He came into the library a little later when I was studying, and we talked some more. I was sitting down at a desk and he was standing up. The recessed squares of the coffered ceiling framed his face beautifully; the scene was so symmetrical. I enjoyed the aesthetic perfection of it all. He thought I was rather too amused by him. I was.

Motion. Movement. Meaning. I watched people moving up and down the escalators in that library for hours. People moved smoothly and diagonally, like they were starring in a line graph. They were literally moving forward. We all were. ‘Forward’ is Birmingham’s motto. That was before things changed and we lost faith in the power of the future, of modernism, of the state, of architects – in fact of anyone who told us to do anything and anyone who tried to make it better for us. We’re all on our own now.

Now the way I felt about that building, the Central Library, will always be different to how Donald feels about it. Women feel buildings differently, just as women feel words differently. My words come from my body; they’re born of me. They have some kind of inner meaning. Words can be female like buildings can be female. Birmingham Central Library is a woman. A grand dame, an Aztec goddess. All the librarians were women too. The architect of Birmingham Central Library was a man, of course. The architects of nearly all modernist buildings were men. But we can’t blame the building for the fact that its designer had a dick. Half a century ago I’d have been typing the notes for some man in a suit – some functionary, rather than typing out my own thoughts and feelings like I’m doing now. Some things have changed for the better, then. But, crucially, these buildings were trying to break us all out of that staid age, to shoot us into a technological future where women would have more value and people wouldn’t be wage slaves anymore. And we’d all live in clean, planned cities packed with buildings that made you go ‘Wow’.

*

The storm had passed. Eyes full of sun. I yawned. A proper night’s sleep – my first proper night’s sleep without Belinda. A gnawing ache ground into my left hip. I heaved myself up, went to the kitchen and made myself a cup of tea – black; I had no milk, of course. Slippers on, out to the garden. I lit a cigarette in slow motion and looked down the garden, away from the house, towards the railway line. The line was tucked away beneath a steep slope behind the garden.

Should I restock the fridge, or should I kill myself?

I sucked on the death stick and sipped my tea. Smoke more? Smoke a hundred a day? My watch said 9:51 a.m. The time trembled on my wrist as the nicotine and caffeine acted like fiends, the numbers a blur. If a train came before 10 a.m. I’d finish the job tonight. Of course I knew there’d be a train just before ten, there always was (except on Sundays). I sat down on a low wall in the garden and stared at a bee dancing around a plant.

10:06 a.m. Engine noise. I rushed to the wooden fence at the back of the garden and peered through a hole in one of the slats. My nostrils started to fill with the faintest tang of diesel. A two-carriage train chuntered past, bound for Worcester Foregate Street. I only saw it for about fifteen seconds, a blur of blue-green metal, a haze and a stammer down in that deep wooded valley.

‘Late. Fucking railways.’ I turned towards the house. ‘It should’ve come before ten. I’ll do it anyway.’ A snail slithered towards me over the paving stones, its movements taking an age, its antennae asking constant questions of the air in front of it. The futility of its journey bewitched me. So slow, so simple to pick off, so tasty, so easy to cycle over by mistake. Pathetic. Accommodating. I loved it. I bent down and stared.

*

Ten Brutalist Buildings

By Belinda Schneider

Chapter Two

Priory Square

I’m not a Sturm und Drang kind of girl – I believe in rationalism and modernity. But rationalism and emotion are not incompatible. Rationalism and fun can be cosy bedfellows. Things that make sense can also be beautiful and enjoyable. Places that make sense can be settings for beautiful and enjoyable experiences. To wit: dancing fills me with glee. Brutalist buildings aren’t always thought of as gleeful locations, but this one is. Why can’t somewhere that’s thoughtful also be a place you can get enthusiastic about, even a place you can get exuberant about? Brutalist buildings aren’t boring, and if they’re cared for they’re not depressing either. This building is called Priory Square, and it has rhythms – like the music you can hear inside. Levels on levels, sharp corners and stacked boxes. They call it a ‘square’ but it’s more like a tiny town wedged into a hill as Birmingham city centre slopes from high ground to low, with shops on top, and below, this wonderful, huge covered den for drinking in live music. The outside of the music venue is just a cliff of concrete, uncompromising and stark and grey and ready to have any experience or any sound imprinted onto it. It’s a blank sheet where you can draw your own fun. This is a building where fun triumphs. Sound, concrete and emotion conspire. It’s neat.

Donald and I went to see The Rationalists play at Priory Square. They were astonishing. I think I fell in love with Donald that night. I thought he might become my husband. He did. We’d got drunk at the pub before the gig – me on gin and him on woeful English lager, which I think was to spite me in some way. He always shouted ‘Prost!’ before the first gulp as a satirical gesture. I asked him why his countrymen couldn’t make beer – or, rather, why his countrymen insisted on drinking the worst of their brewed output while phasing out the breweries around Birmingham that could whip up the half-decent stuff. He always just shrugged his shoulders.

The gig was great. The Rationalists saved their best song, ‘Elizabeth Anderson’, until the encore. Elizabeth Anderson was the name of the girlfriend of the band’s singer, Charlie Sullivan. Ex-girlfriend. They broke up, and forever she’d be remembered by this song. And that song always made me think of that moment and this place. That song made shivers of pure electricity snake up and down my spine when I heard it performed live or listened to it through headphones or on the stereo.

It was such a lilting, beautiful song, so… strung out. Its power built and built from foundations that weren’t so solid. In fact it was made of nothing; it would have probably floated away – that’s how fragile it seemed when it started. So brittle and beautiful. But then as the song progressed it became more potent and more substantial. Those words and those guitar lines just dragged at your soul as you listened. They pulled you into the world that the band were inhabiting, and it was so exciting and bewildering all at once. Tribal and yet gentle, so poignant it made you think of your own life and the important people in it. The best songs always make you think of people – of a person – like the best buildings do. They provoke you and they evoke things from the past at the same time. They tumble up your insides and change the way you feel. And if you don’t feel anything, then something’s wrong. Perhaps you’re too old, because if you’re young you’ll feel things and they’ll mean something to you because they’re important, all this is important, songs are important, architecture is important, all art is important.

Donald pressed his hand into the small of my back as the song began, then he curled it round the top of my hip and squeezed me into him, my head coming to a soft rest on his chest, which moved up and down as he sang the words to the song. I sang them too. And as I sang them I looked around the room and marvelled at the right angles and the space above my head. I’d never been to see a band in a venue where the roof was so high above your head. The Rationalists were from Birmingham, and their songs were only about two things: architecture and love. That’s why I adored them, I guess. My two favourite subjects as well. Why did Donald like them though? He was a cynic, but he had some blind spots.

*

Anguish growled at me. Pity was wired in from heart to brain; lolling sadness permeated body and mind. I couldn’t concentrate on reading or writing. What I wrote was staccato. Disjointed. Small. Pieces. Of a bigger whole. A whole I could no longer comprehend, perhaps a whole I didn’t ever comprehend, and perhaps there was no whole at all? There definitely wasn’t a whole, I knew that. Just bits and pieces. Most of the time all I could do was watch – stupefied, petrified, paralysed, anaesthetised, deadened – as other events took place on a screen in front of me. When I got home last night and wrote about the evening’s horribly failed suicide bid it was the first thing I’d written since Belinda went away. At least last night I began cataloguing what was happening to me. Still, what I’ve begun to document isn’t what you might call a great story; it’s not exactly a compelling narrative. It is a trove of one man’s sadness. It’s not good enough. My work has never been good enough. I’m a writer for regional TV. I need editing. Edit me. Edit this.

I could hardly speak: 218 missed calls on my mobile. I couldn’t face the interrogations of others, however gentle and well-meaning they were.

There was one thing I needed to do. Do right. The pain was too much. I emailed Pete, a telephone engineer I’d been to school with in Moseley a very long time ago. He was kind and quiet, clever and polite. Though there was something behind his mask I could never work out. I bet he’s a spy! Or in the special forces! It would be fine though. He replied immediately, agreeing to the plan. I had to lie and tell him that I needed his help scouting locations for a new TV programme I was writing for.

10 p.m. I glugged a double shot of whisky and caught a bus into town. I had to cross the city centre on foot to get to the place where we’d arranged to meet. But it didn’t take long – Birmingham’s core is disproportionately small for a city whose suburbs stretch for miles and miles and miles. I walked without thinking. It was unreal. What was I doing? Recently, I’ve found myself doing a lot of things that I’m not really sure about – which is strange, because, before all this stuff started happening, I always knew exactly what I was doing. Which was usually ‘failing’, but at least it was failing in a comprehensive, ordered and predictable manner.

So this was almost it. I stood at a crossroads. Not a metaphorical one – I knew exactly what was about to happen in the plot. No, I stood at an actual crossroads. I’d been walking up Newhall Street. Great Charles Street sliced across the road from left to right. I knew that, underneath me, a tunnel carried more traffic – I’d driven through it myself. Dignified Victorian buildings wearing three-piece suits of ornate decoration rose on two sides, 1960s and ’70s office towers on the others. Offices for solicitors and property developers in the new buildings and the old ones. I wasn’t sure exactly where Pete would be. I waited for the green man and crossed the road. A young couple – she in a dress, he in jacket and trousers – walked towards me, deep in conversation with each other, not noticing anything or anyone else. The night was crisp, the air had been paused. No weather, no wind. I pushed on for one more block and turned right into Lionel Street. A few paces down the road and I saw Pete leaning on a silver saloon car, smoking. He saw me and stuck his hand out.

‘Hello, mate.’

‘Hi, Pete. How the hell are you?’

‘Yeah, good thanks. The wife probably thinks I’m having an affair, out at this time on a Tuesday. So we’d better be quick.’ He looked me up and down. Perhaps I should have changed out of the green tracksuit I’d been wearing all day. ‘I hope you don’t mind me saying this, but you look like shit, mate. Everything OK?’

‘Oh yeah, course it is. Just like to, you know, keep it casual sometimes.’

‘There’s casual and then there’s the bloody charity shop.’

I laughed to lighten the mood. I felt like I’d swallowed barbed wire. One of the fears that paralysed me was that I’d break down in front of people. At home by myself it was fine, but I hated getting upset in public. These days I felt like I could go off at any minute. Just one trigger. One little trigger.

‘I heard about Belinda…’

Her name. When I heard her name and we were together it summoned a cocktail of delicious Pavlovian responses: excitement, awe, pleasure, calm, lust, longing, delight. Now it’s the opposite. I felt as if I’d been slashed with a penknife every time I heard the word ‘Belinda’. How many more cuts could I take?

‘It’s awful, really awful. If you ever want to get rat-arsed then you just pick up the phone, you hear me? Any time, Don. Actually, I wouldn’t mind a night off the missus and the kids, so the offer’s there.’

‘Cheers, Pete, I appreciate that.’ I swallowed hard.

‘No problem. So let’s get this sorted then,’ he said, leading me towards the priapic tower. ‘Can’t stay long. You’re sure you want to stop up there all night? It’ll be sodding cold at the top, mate.’

‘Yep,’ I lied, ‘that’s what I need to do – to see the sun come up. We need a location for a sketch… in this new show I’m writing, and I need to make sure this is the right one.’

‘Oh, so you’ll be writing for the telly again? Brilliant. Always watched the shows you wrote, I did. Always. The one set in the planning department…’

‘Big Plans.’

‘That’s it. That was pretty funny. You wouldn’t have thought that a planning department could produce many laughs.’

‘The TV critics agreed – they didn’t think a planning department produced many laughs.’

Pete chuckled warmly at this.

‘Big Plans was only ever shown on Mids TV. Never networked. Did you know that nothing I’ve ever written has been shown outside the region? Spectacular, isn’t it?’

‘Londoners don’t know their arse from their elbow. You’ve got the knack, don’t fret.’

‘Thanks, pal.’

My career as a comedy writer was starting to get back on track, and I was just minutes away from death. The BT Tower loomed above us both. It glowered down at me, provocatively. I bent myself backwards and strained my eyes to catch sight of the top. It looked like a hideously stretched, upended cardboard box which could have been stuffed with a billion sweets to make a rich child’s Christmas present.

Pete rattled some chunky metal keys in the outer door and we were in. There was another locked door to the staircase; he opened it with ease. He flicked a switch and the staircase was illuminated by bare bulbs chucking light against naked concrete walls. Sometimes it stuck, sometimes not. I stared up through the murk.

‘We’re walking!’ he said, beaming masochistically.

It was a pull. When we finally reached the top I was hopelessly out of breath; Pete was too. The pair of us stood there wheezing – two men in their forties who were utterly past it. Sweat dripped from Pete’s greying hair and fell across a stretched face that was starting to wrinkle. Did I have wrinkles? I couldn’t look in the mirror anymore.

‘Ciggie?’ Pete offered.

‘Fuck it,’ I said, taking one.

‘Built in 1962, this was.’ Pete exhaled. ‘Tallest building in the city.’

We sat in silence, staring out at the twinkling lights of Birmingham – from this height it appeared as an ocean of warm neon contrasting sharply with the blackness. The amber light bobbled and jostled against itself. In the distance, to the north, a river of lights ran both ways the full length of the horizon. Pete must have clocked me looking puzzled.

‘The M6.’

‘Ah right. I was wondering.’

In the still of the windless night the city suddenly looked more relaxed, more sure of itself. We were surrounded at the top of the tower by a more chaotic scene: aerials, vast circular satellite dishes, boxes of equipment, coloured wires. Pete gently said his goodbyes and walked back down the steps. In my ears: his feet stomping against cold hard concrete, all the way to the bottom; echoes; the clanking of metal. I thought I’d give it half an hour first.

I was mesmerised by what lay before me. But it was nothing without her. I was scared by the depth of love I’d felt for her, the amount I missed her when she was away speaking at events or visiting buildings abroad, the daydreams about her I kept having when she was away. Now my love for her has unfolded, spread out into sticky desperation and boring grief that stretches beyond every horizon. Beyond Sutton Coldfield in one direction and the Lickey Hills in the other. That far. As far as I could see. So far. What was a tightly wound bundle of feelings we shared and nurtured is just a flat, featureless desert of memories and despair. No direction, no thought, no shape. I would give up everything to change things, to change the ending. Everything so futile. Liquid poured into my eyes, then out down my cheeks. The view became wobbly and ill-defined.

Calm descended after half an hour. I fudged the right arm of my shirt across my face to erase the tears and the snot, and I stood up by the ledge. I looked out across a tarmac-bottomed canyon. On my right a giant ‘M’ smiled out from the crown of the Mids TV Tower, the point I’d jumped from before. This would work out better. It was cleaner this time, more serious, less dramatic. I didn’t hesitate.

I said, ‘I’ll be with you soon, darling. I love you.’

And I stepped off the top of the tower.

But here’s the funny thing: I didn’t feel myself falling. My eyes were screwed tightly shut as I realised that. So at first I couldn’t confirm my sense that I wasn’t falling. I opened them and saw Lionel Street thirty-one floors below. It was moving very gently forwards and backwards. Was I dead already? I turned round and immediately it became obvious that my belt had caught on an aerial and I was dangling over the edge.

‘Jesus Christ,’ I mumbled, scarcely able to believe it. And then, as I looked back to where my belt was caught, I felt a warm jet of liquid land on my left cheek and forehead. Confused, I made to wipe it with my hand. It was white, sticky. I saw an enormous shadowy bird swooping majestically above me, having just squeezed a piping-hot shot of ornithological effluent all over me. A peregrine falcon. I knew there was a pair living on top of the tower. It crowed and flapped away in triumph. A few minutes later it returned with its mate. They perched side by side on a satellite dish right above my head. I could hear their feathers ruffle as they shook their wings and folded them in.

Using my last reserves of strength, I hauled myself back up onto the balcony on which I’d just been sitting, careful not to let my belt snap. I sighed, crawled into a ball and drifted off.

At dawn I was woken by a light so blinding and a sunrise so brilliant that I thought I’d been born again. I squinted towards the east as the sun rose above the city. It was a cold morning, icy and full of promise. I don’t know how the cold didn’t wake me up. I felt bemused. Maybe it was time for the suicides to stop.

Pete arrived at 7 a.m. and let me out into the street. If I’d done it properly he’d just have found a stain on the pavement. And entrails in the canal. I promised I’d go for a drink with him soon. He didn’t suspect a thing. I bought a cinnamon pastry and nibbled it very slowly as I walked back towards the bus stop on Moor Street. I concentrated on each sweet mouthful, but my chewing provoked only a feeling of ambivalence. I caught a bus home, and once inside I went straight up to my office on the first floor. I reached to take my diary off my desk but stumbled a little through tiredness. I knocked very gently into the bookcase, and it wobbled. A single photo fell from the top shelf and floated down to the floor in slow motion.

I picked the photo up and stared at it. The photo showed Belinda standing among a forest of grey pillars. I stared intently at her auburn hair and her blue eyes, at her cheekbones and her full, pink lips. She wore a short-sleeved top and a knee-length skirt. The palm of her left hand was resting on one of the pillars. She had a handbag slung over her shoulder and carried a bottle of water and a camera in her right hand. The location was the Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas – the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. The picture was taken in the afternoon, at about 3 p.m. You can make out bolshy sunlight, make out shadows cast by the pillars. The shot is almost perfectly framed, save for a blonde woman wearing sunglasses and standing in the background. I didn’t remember her being there.

It was quite a day. Seven hours later, as we were finishing dinner at a restaurant in Hackescher Markt, I’d got down on one knee, pulled out a ring and asked Belinda to marry me. She said, ‘I can’t believe you’re doing this. I’m in shock. Of course I’ll marry you, Donald. I want to be with you forever.’ We kissed and hugged, and the waitresses – seeing what was going on – began to clap. One waitress brought out schnapps, and even our shy fellow diners – strangers, Germans, tourists from Scandinavia and Britain – joined us in a toast. They yelled, ‘Auf Euch’, and Belinda and I replied, ‘Auf Uns!’ Sometimes, even though you’re aware the earth is still spinning, it feels for a moment as if it’s stopped for you, and you don’t have to feel dizzy anymore. That’s how I felt during that entire day.

The photo was one of my fondest memories of my and Belinda’s life together. I delicately placed it on my pillow and lay on the bed next to her for an hour. Thoughts spun through my head: reminiscences, conversations, ideas, plans.

I went downstairs and fished around for a VHS tape in a cardboard box under the stairs. I went over to the VHS player and stuck it in. The machine swallowed the cassette greedily and a fuzzy picture emerged on the TV.

Welcome To The Masshouse. A light entertainment series – with jokes and comedy sketches that I wrote. The title? A wheeze that only Brummies would get – there is a small pie-slice of Birmingham city centre called Masshouse. The title of the show is a play on ‘Madhouse’ and cocks a snook at the ‘craziness’ of the planners who, in the 1960s, created a city some people felt was a place that could only have been built by the insane, for the insane – a place whose false monumentality would eventually drive all of us insane too. Masshouse was a fool‘s paradise of interlocking platforms, decks, dual carriageways and subways, which provoked a primal scream in people who got lost within the confines of its damp walls and blackened ceilings. I was shocked by it, drawn to it – and unable to figure out quite why. Like so much of my home city, this piece of a place doesn’t exist anymore. The roundabout, the motorway, the slip roads, the subways: all wiped off the map. Now in their place: car parks, waste ground, some tall residential blocks for yuppies.

*

[Countdown clock]

[Title music – jaunty and insistent, like the soundtrack to a fair pulling into town. Scenes of Birmingham play out in the background, but they all look grotty to my cynical eyes – motorways, underpasses, tower blocks, concrete boxes. And between these shots are stabs from previous editions of Welcome To The Masshouse depicting bizarre moving tableaux – lots of people dressed in chicken costumes, custard pies being thrown, fat men appearing to be telling jokes – though you can’t tell what they’re saying as they’re mute, thank God.]

Title card – WELCOME TO THE MASSHOUSE

Voiceover: ‘Welcome to the Masshouse! This week we ask Brummies whether [inaudible due to dodgy tape recording] really want to see another [inaudible, screen goes fuzzy and the picture sort of drips downwards, resolving into squiggles, then suddenly returns to normal] built? And, can foreign visitors to Birmingham do a little bit of Brummie on camera for us? We’ll see, bab!’

*

Welcome To The Masshouse aired late on Friday nights in the so-called ‘post-pub’ slot, but only on Mids TV, never networked. I guess viewers in other regions wouldn’t have got the punny title. But I’ve no doubt they’d have immediately understood the base humour of the show itself. Even a child could understand that. I skipped through the video using the fast forward button until I came to a part I wanted to watch.

*

[Cut to a human-sized chicken asking foreign visitors – fuck knows how we found any of those back then – if they could a) understand a Brummie accent and b) replicate one. Concrete in the background – definitely Birmingham Central Library. Which idiot is wearing the chicken costume this time? Oh… it’s me. Camera pans round to reveal a woman with honey-coloured hair sitting on a bench, looking right down the lens with the most intense stare. She’s puffing away, obviously. Pan left. An equally beautiful young woman with chestnut hair and twinkling blue eyes, smoking with equal fervour; she’s also staring at something. She has a book on her lap but I can’t make out the title. Something about… the future?]

[The chicken asks the brunette – the one who we just glimpsed – if she can do a Brummie accent. She makes a good fist of saying ‘Y’oright bab!’ before collapsing into giggles. She has a thick German accent. The chicken asks her why she’s in Birmingham, and she says she’s an architecture student; she’s also working as a barmaid at a pub in ‘Moseley Willage.’]

*

I paused the video and sat there for a while, transfixed by pixels on the flickering screen. The girl’s smile was freeze-framed, as if the world had ended and all that remained was happiness and youth. A train came past just before 10 a.m.

All the time that Belinda was considering the sublimity, or not, of spaces and the man-made monuments of the next thousand years (or as it happened, rather fewer years), I was writing gags about fucking chickens crossing fucking roundabouts. Or about men in planning offices deciding where to put roundabouts – which was my highbrow period. Or else I was dressed in costume, harassing people in the middle of a roundabout in Birmingham city centre for a light entertainment programme on regional TV.

I spent the rest of the day lying on the couch, bumpy cushions underneath me, hard armrest against my head. Sometimes I thought about various odd concepts that had intrigued me for years, and sometimes my mind was as empty as my fridge. I rolled from side to side on occasions. The clatter of trains passing every few hours broke the day into sections. The noise they produced – the rumble and the growl of a diesel engine having power applied; sometimes a whistle too – gave me a fleeting feeling of well-being that few other things could provide right now. This behaviour was becoming habitual. Every day. Just lying, or sitting, just watching life pass me by. Frozen. Unable to relate, unable to understand, unable to function. I knew the world was continuing around me, but it seemed to be on pause here in the house. I seemed to be on pause. Even the few things I actually did seemed laboured – a trip to the kitchen or the bathroom. Both felt like they took an hour. I couldn’t get excited about anything. I didn’t want to see anyone – well, there was one person I wanted to see, but that was out of the question now. The emptiness is a blue whale that swallows you whole. When you’re inside the creature’s belly every sensation is muffled; taste and smell and sight and sound are dulled. It’s impossible to get yourself back until the creature shits you out.

Night fell. I summoned up some courage to walk to the supermarket in the centre of Moseley. As usual, the lights were turned up to full. Bastards. Was I in heaven? No. The end was the end. With a head full of metaphysical conundrums I negotiated the crisps and dips. Though actually, what was Moseley if not a kind of earthly heaven? I used to love living here with Belinda, us sharing a house and a life in this cute Victorian village (which was actually just a ‘suburb’ with delusions of grandeur. It wasn’t surrounded by fields as villages must always be). Belinda, of course, thought Moseley’s architecture was too twee and too timid. But she bit her lip and indulged me. She liked the bohemian feel here at least, and the Middle Eastern deli where she could get Turkish spices that reminded her of the food she once enjoyed in Berlin’s immigrant cafes. I think she’d secretly developed a crush on Moseley when she was a barmaid at the Bride of Bescot in her student days. The Bride was, coincidentally, also my local.If you are in the mood to try salsa, then buy pineaple salsa from here, which is amazing.

A four-pack of lagers and some triangular Mexican-style crisps went sailing into a blue plastic basket. For about five minutes I dallied over whether to buy a jar of salsa too. Realising how trivial the internal discussion in my head was, I decided to beat myself once and for all. I extended my right arm and scooped every jar of salsa from the shoulder-height shelf into my basket. A woman standing near me, examining the ingredients of some breakfast cereal, turned and looked aghast. My right arm stretched painfully under the weight of a basket which now contained twenty-five jars of salsa – the shop’s entire stock. The basket’s handle bent.

Ayesha, the friendly checkout girl, looked me up and down briefly. ‘That’s a lot of salsa, Donald. Are you having a party?’ A sly wink. A licked lip.

‘I am, Ayesha,’ I lied. ‘Can you get me a bottle of single malt from up there too?’

‘Of course,’ she said, reaching, winking. ‘If I’m invited…’

I paid up and walked home with the heavy load and a heavy heart. Once I was back and safely ensconced on the sofa, I started eating the spicy tomato salsa with a tablespoon, but two jars was enough. I felt sick. I drank three of the cans of lager, said, ‘Prost!’ with guttural gusto, and wiped some tears away with my sleeve.

*

How can you describe what’s not there? I guess it’s my job as a writer to find a way, but it just doesn’t seem possible right now. How can words do justice to emptiness, nothingness? Photos contain fragments of truths, pieces of memories. They show lives paused. They’re more real than words because you can’t edit them or misremember them. Videos are even better because the memories move; they’re alive. Ultimately, everything that tries to capture a mood or a moment is an imperfect snapshot of a place, a time, an emotion. But if that’s all we have…

Belinda will always live on inside these photos. I held one, staring at it, staring into Belinda’s eyes, into her soul. And at her body, I must admit. Belinda is lying on her back on a Sardinian beach, her face turned towards the camera, her mouth open, her lips slicked and rouged. She’s smiling. The frame crops out everything below her stomach. The sun is in her eyes and they’re barely open. She’s holding up a hand to shield them, her nails red, a ring on the third finger of her left hand – my ring. Her white bikini top strains. Greenery licks the back of the beach.

I put the photo down, went downstairs, swallowed a couple of painkillers and some whisky, and stuffed a handful of triangular Mexican-style crisps into my mouth, crunching down, my mouth filling with the disgusting tang of sweaty pseudo-cheese. I exhaled deeply and lay down on my back on the living room floor, blinking, thinking. I put my right arm up against my forehead. The small terraced house had felt like my castle keep. I wrote here when the studios became too boisterous. This was the place I could always retreat to; these were the walls that always seemed to deliver the jokes the script needed – however shit those jokes turned out to be in the final edit. Four walls. Two bedrooms. One living room. My office upstairs. A little garden and a railway line down beyond it. The front door was yellow, and the tiles on the hallway floor were exquisite Edwardian monochrome. And when Belinda moved in with me, the sun always shone through the windows set into the door, shone through coloured panes and projected a warm glow, shone into the hall, shone into the house, shone into my heart. And I found myself caring a little less about regional TV programmes and average-at-best jokes, and a little more about architecture and love, which were her two preoccupations. And to those preoccupations a third was eventually added: me. Feeling so treasured by someone was an addictive sensation, a rare sensation. And now I was having to go cold turkey in the most brutal way possible.

*

Ten Brutalist Buildings

By Belinda Schneider

Chapter Three

St Agnes Kirche, Berlin

The happiest day of my life took place here in Berlin. My husband and I got married at St Agnes Kirche in Kreuzberg. Go and see this place for yourself. Touch its walls. Think about it.

I heard about it when I was a teenager. We smoked cigarettes in a park where there were bushes you could hide in. It was our space, one of the few private spaces we had in a society that watched everything you did. A boy told me about seeing this blank-faced church in Kreuzberg, near to his family’s house. I can’t remember exactly who it was, but he knew one of my friends. I was intrigued – by his discovery, and by him. His family lived in the west, and so when he crossed over to our side he must have been shocked by us, by everything. He didn’t snarl like most boys I knew, I remember that. All the boys on our side were being prepped to join the army and kill ‘fascists’. In West Berlin you didn’t even have to do National Service; you could drop out and play in a band or do anything you wanted. He spoke softly and slowly. When he started talking about this strange thing, this weird building, it pushed a button somewhere inside me. I wanted to surround myself with art and explore the worlds that I couldn’t explore. Me and my friends told each other stories; we asked each other about our fantasies. When our contemporaries from the west came – like this boy – it made the possibility of an escape one day seem possible. Sitting in those bushes, it was all so profound, being caught between childhood and adulthood. We talked about boys, of course. There weren’t many I liked around Lichtenberg, just the ones who had some idea of a bigger world and a cultural life. Usually their parents were creatives. I didn’t like the boys whose dads were one of Die Grünen – the Volkspolizei – I was scared to speak when they were around, lest things be reported.

There was so little real art in East Berlin, aside from the state galleries we’d be shepherded round, and the pointless cultural centres. Real creativity was stifled. We had to retreat into our minds. I wandered round by myself and felt spaces, explored spaces, believed in spaces. Whether it was a caged bridge over a road or that little shrubbery in the park where we smoked cigarettes and giggled about boys. My inner monologue tried to make those spaces bigger than they were so I had some room to move.

But we were Berliners – we were outcasts and we were dreamers, we were wanderers and we were wonderers. My mother told me about how Berlin had always been a refuge for free-thinkers, for subversives, for those who wanted to live outside the normal mores. She told me about the Jews who hid in the forest through the entire Second World War; she told me about our friends who tunnelled to the west to escape the stifling atmosphere and the fear, about the gays and the punks and the people who wanted to find their liberation in Berlin, about how Berlin began as an industrial city, about how people were offered their freedom here, about how a quest for enlightenment had defined the city throughout its whole history.

I wanted to grow, we all did. We talked about what we might do when we got older and what we might see, but we knew there’d be trouble if we talked too much about that kind of thing: Das war die DDR. But no one could stop you talking about boys, blushing about boys. One day we played a game of listing all the things we thought our first boyfriend would have. I chose kindness, a handsome face, blonde hair, creativity – a boy who wanted to be an artist or perhaps a writer. My friends were perplexed by this.

‘Why would you want a boyfriend who writes? He’d be sitting on his own all the time, he wouldn’t have time to take you out. How about one who makes things with his hands and works 8–4?’

It was a silly game because it wasn’t even something any of us wanted then. We were just playing around with the notion of having a boyfriend – to look older than we were, to fantasise together about what it would be like when we were finally in control of our own lives.

‘Yes,’ I said, smoking, waving my cigarette and fluttering my eyelashes. ‘A blonde boy who writes. I’d marry him at St Agnes Kirche. The wall will have come down by then.’

Gasps. ‘You can’t say that! It’s an anti-fascist, counter-revolutionary protection barrier to guarantee our safety!’

‘Bricks should be our salvation, not our imprisonment.’ It made me laugh. It also made me scared. I smoked more. ‘Definitely blonde.’

The first time I crossed into West Berlin – just after the wall fell – I didn’t know where the hell I was. It was new territory. My mother told me to head past that hulking building that held the offices for the right-leaning newspapers of West Germany and eventually I’d find what I was looking for. And I did find it. I found the church – which, sadly, had rubbish bags strewn around it. St Agnes Kirche. It was plain, so plain that you could project your own thoughts onto the campanile just like a cinema projector shows a film against a white wall in a classroom. I ran my hands all over the porridgey exterior of the building and then I ran inside. The priest saw me and raised his eyebrows. He said he didn’t know me, and I said, ‘Of course, I’m an Ossie!’ He said, ‘Bless you, my child,’ and fetched me a barley water and asked me how it felt to be here and did they let us pray and were the Stasi real and did they and really and how did we and why and… I looked at the ground as I confessed that I didn’t believe in God but in people, though if one building could convince me to change my mind then this would be it. He laughed and said it wasn’t a problem, I was welcome any time. The priest asked what I was going to do next, and I said I wanted to try a banana but I didn’t have any Deutsche Marks. He went back to the rectory and brought out a banana. I said, ‘Danke!’ Peeling it seemed so odd, the custard-coloured flesh seemed so soft.

I felt drunk. It wasn’t the barley water the priest gave me – I was drunk on hope, excitement. That day thousands of East Berliners just ran round West Berlin. I jogged to Potsdamer Platz and then across the Tiergarten. I actually jogged. Walking was not fast enough. I had sneakers on so it was OK, and that first banana – which tasted weird, but nice all the same – gave me more energy. But the day was warm. How did I find my way? On the maps we were given, Berlin didn’t exist on the wrong side of the wall; it was just a blank, just cream space, just nothing. In reality the blank space more accurately reflected the real state of our side. I got to Interbau and I didn’t know where to start. I’d read about it in my parents’ books. I ran one way then the other, looking at the blocks of flats that the great architects had built for pure propaganda purposes to show that West Was Best. But they’d lied to us in the east and told us in the newspapers and on the state TV that Interbau was decadent and not Marxist; millionaires had moved in and spoiled the for-the-people rationale. Not true. But to me it was more socialist than the plattenbau blocks in Lichtenberg that we lived in. They were rows of emptiness. Prefabs. They would fall like a house of cards if you blew on them. At Interbau the blocks were strong and manly, like a built version of my blonde boy, the one I’d kiss one day. These blocks were handsome, and the gardens blended in so nicely with the strong architecture. The flats were homes for normal people, not millionaires – they were socialist. But they were beautiful. If only people could sieve out the plattenbau rubbish when they think of modern architecture and see the beauty of the bespoke buildings put up with such love. They might change their minds. I was so tired after running round the Interbau, so tired after St Agnes, so tired after weeks of hope and years of fear, so tired of chasing and hoping, so tired of everything, that I laid my head down in the Tiergarten. And I fell asleep. And I dreamed of England, because as much as I was free in my homeland, it was too small and too Teutonic for me. I needed to see something different. I would be going to England to study. To an England that even Englishmen don’t go to – to the middle of England, to the best of England, to Birmingham. Not London. And perhaps because it rather reminded me of my home town, I felt happy there from almost the moment I arrived.

*

You probably don’t know what’s it like to lie prone in bed or on the sofa, morning after morning, afternoon after afternoon, doing nothing, just feeling the duvet or the cushions smudge against you – the only touch you’re likely to get. Nothing. No movement, no contact, no progression. Or maybe you do?

Jowls squeezed against cushion, cheeks crushed against sheets, arms by sides, stomach so flat because I wasn’t putting anything into it aside from booze and nicotine and snacks. Each blink lasted a minute, more time with eyelids shut than open. Breathing rate plummeted, I could hear and feel every long, drawn-out breath. A strange insensitivity – cut fingers and bleeding gums emitted the same dark fluid, but physical pain didn’t turn up to the party.

Moving hands and digital displays marked time in an aggressive way, the ticks baying at me. The radio alarm clock on the bedside table seemed particularly malicious, with its red, robotic numerals. Me and that machine were at war. Ten minutes I’d say, fifteen minutes I’d say, then I’d get up. Then I’d be cured – for a little while. Ten more, five more. Sometimes the snooze button, sometimes the infernal beeps yelling at me to GET UP. I’d stare at the wall, at the ceiling, through the window at the sparrows and at next door’s cat, who was also staring at the sparrows with a murderous glint in his eyes. Sometimes I’d smoke outside and contemplate clambering down onto the railway tracks. The gradient was almost vertical, the drop more than a two-storey house.

I wrinkled my nose; I frowned. Here’s where Bel did Pilates. Here’s where Bel wrote. Here’s where we fucked. All in the past. It was a disconsolate soap opera with no resolution. I could write this up. Many Mids TV viewers must be sad or old. The majority of daytime viewers, surely? And if that was true then maybe there was a market for a soap opera where the characters just eke out a pathetic existence, where they succumb to pressure and just lie there doing precisely sod all. That could work. I’d suggest it to Bob next time I saw him. Something really sad, really pathetic. Oh, but it’d have to be sadder than the saddest thing you could think of. I hope you know that feeling. I hope you’ve known it at least once.

My eyes were drawn to our bookshelves. My novels, her books about the world. So many of my books were funny or sad (I thought that writers who could blend both together were really hitting the sweet spot). So many of Bel’s books were about utopia and optimism, about how ideas could work and how people were ready to adapt to new worlds.

Belinda had thought I fostered a climate of cynicism which had led us to lose any belief in doing better by everyone, in thinking we could build nicer cities for all with incredible, ambitious buildings sitting at their heart. Sure, it was my job to take the piss out of people, out of the stupid things we saw every day. I told her satire was very different to blind cynicism. We had playful arguments. I told her that, today, people thought all authority was bullshit – whether it was benign leftist or malign rightist. Once when we were in London on a trip to see one of her beloved concrete monstrosities, I told her that people just wanted to do their own damn thing and that individualism wasn’t necessarily part of the capitalist conspiracy, was it? It’s just the counter-culture. Think of the freedom we have now: we don’t have to live or love in any way we don’t want to. All social barriers have come down. Grand narratives are for the past. We just do whatever we want in whatever city in whatever country we want, and we don’t listen to anyone. We especially don’t listen to anyone who thinks they can dictate our lives or rebuild our cities. And surely, as she came from a totalitarian state, she knew the importance of freedom? My job was to prick pomposity. My job was to take the piss. My job was to be against all authority in all of all authority’s multifarious forms. This is what I said. She’d make her eyes expand as much as she could and call me a ‘fucking anarchist’ with a look of mock horror, then she’d crease up with laughter, take her top off in one motion, sidle over and kiss me.

Ten Brutalist Buildings

By Belinda Schneider

Chapter Four

Eros House

We were in South London. I wanted Donald to kiss me up against Eros House. I wanted to feel his hands around my waist. I thought it would be funny. Actually it felt better than that. It was sensual to experience the concrete cheese-gratering up and down my back, to place my hands on that rough exterior, to feel hot breath on me and smell his sweat, the beer and the cigarettes and the lust when he half opened his mouth and looked down at me.

We went to the top of the Catford Centre car park afterwards and drank cans of cider. He thought it was a ‘concrete monstrosity’. He was joking – mostly. There were all these French paperbacks lying around on the car park decks – books by Baudelaire, Camus, Houellebecq. It was very strange. These things don’t happen by chance. Each end result is the end result of a complex chain of events. So what was going on here? Who had been here? What was the building trying to tell me? What was it trying to tell us all? I loved that place. It was no-nonsense. I got drunk pretty quickly. We started talking about politics and about comedy. About how attitudes in society shape attitudes to things, to art, to architecture, to TV. Donald said to me, ‘People just want to do their own damn thing. Individualism isn’t necessarily part of the capitalist conspiracy, is it?’ I told him he was a fucking anarchist and I seduced him again.

Did you like that bit? I hope so. I’m trying to write something here that’ll make you sit up and think. Call it criticism if you want – maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. Don’t assume that all architectural criticism has to be as pointed as ‘This is a good column’ and ‘That is a bad pediment’. Break through the walls of words and the words of walls. Examine and feel. Brutalist buildings are the ones that precisely lend themselves to this state of intimacy, an intimacy between space, people and words. They provoke. They provoke you. They provoke me. Prod them back. They’re beasts, they can take it. Experience what’s being meant by the building, however abstracted the thought might seem or the building might look. And when you’ve done that, for pity’s sake just go and enjoy the damn place. What’s wrong with going to a multi-storey car park and making art or getting drunk or holding a rave, or fucking, or reading French paperbacks? Nothing. It’s your space – get out of the house more and use it. Buildings love to be loved, like people.

*

Another afternoon lying on the sofa. I felt myself drifting off. My heart tapped out the faintest tick-tock like a shy clock. My breathing was laboured like an old man’s. So it’s no wonder that I slipped into yet another make-believe world.

*

This is a dream:

I can see dead people. The people who used to live in buildings. And seeing dead people suddenly seems to bring these dead buildings back to life. I’m in a flat. They’re everywhere. All the people that lived here. It’s like being in some kind of computer game. They fuss around but they don’t bump into each other. They don’t even seem like they can see each other. Next I’m in Priory Square. Dead shoppers are milling around. A guy is walking round the roof. He pauses for a moment, looks down, then throws himself off. I wake up sweating; my stomach aches.